Category: Blog

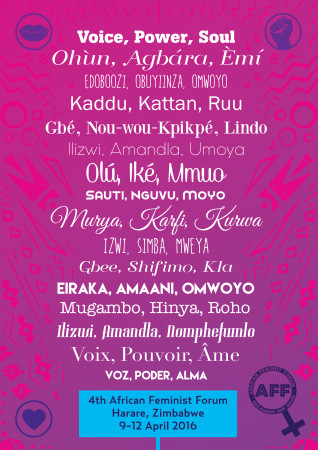

Fourth African Feminist Forum:VOICE POWER AND SOUL, Harare, Zimbabwe 9-12 April, 2016

Fourth African Feminist Forum:VOICE POWER AND SOUL, Harare, Zimbabwe 9-12 April, 2016

4th AFRICAN FEMINIST FORUM

4th AFRICAN FEMINIST FORUM

Harare, Zimbabwe April 9-12, 2016

It’s finally here! AWDF is honored to be hosting the fourth regional African Feminist Forum (AFF) in Harare, Zimbabwe from 10-12 April 2016 under the theme: African Feminism: Voice, Power and Soul.

The forum will be preceded by a pre-forum of feminists from Francophone Africa, who will meet on April 9. This year, AFF is being organized in partnership with the Zimbabwe Feminist Forum and coordinated by the Zimbabwe Women’s Resource Centre and Network (ZWRCN).

Over 170 feminists from all over Africa will be attending this power charged programme which will include:

- Plenaries- to set the context, take stock and identify areas of strategic concern around politics, economics and society.

- Breakout sessions- for more in-depth strategizing on the key themes

- Skills sharing– sessions where feminists specialists train participants

- The Great Debate- a highly participatory debate on a contentious issue within feminism

- Wellness space– one-on-one and group sessions focused on physical and emotional health and wellbeing.

- Arts programming– showcasing African feminist art-activism

Each of the three days of the forum will be dedicated to Zimbabwean feminists ancestors Day 1: Chiwoniso Maraire singer, mbira player and advocate of social justice. Day 2: Award-winning writer Yvonne Vera, and Day 3: Freedom Nyamubaya, freedom-fighter, poet, dancer and farmer.

The African Feminist Forum (AFF) regional gathering brings together African feminist activists to discuss strategy, refine approaches and develop stronger networks to advance women’s rights in Africa.

For more information, please check out the relaunched African Feminist Forum website at: www.africanfeministforum.com

Nigerian Feminist Forum Reacts : The Gender and Equal Opportunities Bill.

Nigerian Feminist Forum Reacts : The Gender and Equal Opportunities Bill.

- Swiftly reintroduce the Gender and Equal Opportunities Bill for an informed debate on the floor of the chambers;

- Reintroduce the GEOB into the Senate on the Executive and not Residual list. We are tired of having laws pertaining to women applicable only in ABUJA.

- Consult members of civil society organizations (CSOs) specifically the women’s movement for better analysis & informed positions on the gender & equal opportunities Bill.

- Pass without delay, the Gender and Equal Opportunities Bill when re-introduced for reading at the floor of the legislative chambers

- Continue to support and sustain media advocacy needed for the successful passing of the GEOB and;

- Keep issues concerning the welfare of women in the front pages of the news.

- Sustain social media campaigns and engagements on issues affecting women in Nigeria;

- Come out en-masse on Wednesday the 23rd of March 2016 by 10am at the Lagos Television (LTV) compound, for a peaceful protest against the withdrawal of the GEOB. (Dress Code is Black T-shirt/Blouse/Hijab/Skirt/

Trouser) - We also encourage CSO’s and individuals outside of Lagos to organize and carry out similar peacefully protest in various cities.

International Women’s Week: A celebration of Voices and Truths.

International Women’s Week: A celebration of Voices and Truths.

At AWDF we recognize the importance of celebrating women in our daily lives and during the month of March we especially invite the public to join us in this joyous task. This year, we marked the day with three special events, each of which had a strong recurring theme: Voices and Truth.

AWDF believes conversations like these are vital to changing stereotypical notions about African women and their role in society.

Renowned Ghanaian photographer Nana Kofi Acquah’s photo exhibit “Don’t Call Me Beautiful,” was a work that focused on displaying the complexity and variety of the African woman, and in that vein it definitely succeeded. AWDF held a panel discussion at the close of the exhibition, on 8th March – International Women’s Day – to explore these themes and to question the relevancy of the word resilience in connection to the African woman. The event took place at Alliance Francaise Accra.

The room was filled with members and staff of Alliance Francaise Accra and an engaged public. At times contentious, never dull, the panel, which was moderated by Kinna Likimanni, discussed notions of beauty, colour and skin bleaching, with active participation from the audience.

Our second panel discussion organized jointly with the Centre For Gender Studies and Advocacy ( CEGENSA) on Friday March 11 was another opportunity to tackle thorny issues.

The theme “About Last Night,” focused heavily on student relationships, date rape, and sexual abuse on Legon Campus and the ways in which victims are treated both by the institution and their peers. The room was full of students from the University and some students from SOS-Hermann Gmeiner International College. A few young undergraduate women were brave enough to share harrowing stories of their own abuse that they’d suffered on Legon Campus and the lack of response that followed it.

“He walks around here like this untouchable, charming guy and no one knows that this is what he really is,” said a young woman about the male student friend who assaulted her.

And she was not the only one– many students and people in the room expressed the unfairness of society’s expectations for young girls and the need for women to be the ones who guard themselves from sexual assault. It was clear that there was much to discuss, and the event ended on a note of bittersweet hope for all involved.

One high note was the presence of the SOS students (all female), whose vocal and confident contributions underlined their heightened self-awareness and knowledge of women’s rights and feminism.

“They were the real stars of tonight. They absolutely made my day – and the entire programme,” said Prof. Audrey Gadzekpo, who acted as moderator for the discussion.

We wrapped up the week with a celebration of music at Accra’s cultural mecca Alliance Francaise, where the Francophonie festival began with a concert by Malian singer Fatoumata Diarawa.

At AWDF we recognize the importance of the arts as a tool to promote social justice and a medium to nurture and raise the profile of African women and their achievements. Teaming up with Alliance Francaise and other partners for Diawarra’s concert was a way in which we could salute one of the continent’s brightest talents.

After a soulful curtain opener by AWDF’s communications staffer “Suga” and high-energy Ghanaian musician Sherifa Gunu, Fatoumata hit the stage for an unforgettable night of music and dance. Two of Fatoumata’s songs, “Oumou” which celebrates African Female Artistes and “Boloko,” a song with a strong anti FGM message, reinforced the power of music as a tool for social change.

From the various ways in which we portray women in art to the lives women lead in silence, these events examined the truth of African women, finding it painful, complicated and inspiring.

African women and their achievements and struggles must be celebrated and discussed. And the spirit of International Women’s Day, that week and month must be carried through the entire year if we are to reach the goal of gender parity. For us at AWDF we will continue to strive to see that women are understood as deserving of recognition, celebration and a voice.

A Fire to Transform This World: A Perspective on Sexual Health and Rights

A Fire to Transform This World: A Perspective on Sexual Health and Rights

By Belinda Amankwah

“I remember when I was growing up, my mom told me I like to play too much and that I shouldn’t play with my brothers. She said I was to help her in the kitchen. So she would wake me up early in the morning whilst my brothers were still in bed to sweep the compound and do some other house chores. So I asked my mother why my brothers won’t join me to do the house chores and she said it is because I am a woman and that’s my job. This was when I realized that I was different and society had different expectations from what they had for men.” – ACSHR Participant

The 7th Africa Conference on Sexual Health and Rights (ACSHR) was held at the Accra International Conference Center this month. AWDF and Curious Minds hosted a Young Women’s Pre-Conference on 9th February, 2016 to provide a safe space for feminist engagement and knowledge sharing on the topic of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR).

According to the organizers, ACSHR’s vision is “part of a long-term process of building and fostering regional dialogue on sexual health and rights that leads to concrete actions and enhance stakeholders’ ability to influence policy and programming in favour of a sexually- healthy continent.”

The conference saw the gathering of many young women from different countries around the continent, mostly between the ages of 15- 30. The venue was almost filled to capacity by the time the conference started. The young women looked happy to be together, enthusiastic about the day and the atmosphere was very blissful. Many were striking an acquaintance with other young women and getting to understand the environment.

As a young women’s rights activist, it was a great experience attending this meeting. I met many intelligent and passionate young feminists, women’s rights activists and a few veterans in the African Feminist movement. The sessions were well delivered as the facilitators did not only present information but also made the experience very interactive. This gave young women the opportunity to share their thoughts and experiences freely – more so than they would have had the chance to in other spaces.

The first session focused on the foundations of African Feminism. The facilitator, Jessica Horn, Director of Programmes at AWDF and a feminist activist, spoke on the principles, theories and practice of feminism. She started by throwing this question to the audience: “When did you first know you were a woman and that you were different?” This exercise was done in small groups, giving us the opportunity to listen to some interesting stories and lessons. For me, what I heard most was that being a woman comes with a lot of expectations that sometimes do not allow women to develop themselves to their full desired potential, especially outside the home. However, being a woman surely has positive results, too.

Here is another story shared in my group:

“When it was time for me to go to college, my father paid my fees and provided me with everything I needed but when it was my brother’s turn to go to college, things got financially difficult and my brother had to work to pay his fees. My dad still continued to pay my fees. He said, a man is supposed to provide for himself and a woman is to be taken care of.”

I have a memory from my childhood. My brother and I are very close in age and we would fight over any and everything. Every time we fought, my mom would tell me I am too tough. She said women should be emotionally and physically soft and should not fight. So I kept on asking myself, “Why should I intentionally allow my brother to beat me when I am capable of fighting back?” I understood at an early age that this showed the world that I was a woman.

A highlight during the workshop for me was when Juliana Lunguzi, a woman MP from Malawi, was invited to share some motivating words. She told us about her struggles as a member of Parliament but also reminded us of the need to support girls throughout their education. She said, “UNICEF, Action Aid and other organisations are building schools but no one is paying the fees of these young girls to attend school, and for me, that is the most important thing. In our fight for the rights of women and equal opportunities, we should remember that it is through education that young women can occupy and share the spaces we are fighting to create for them.”

I enjoyed the session by Cecilia Senoo (Executive Director for Hope for Future Generations) on how Feminism intersects with SRHR. I particularly loved the interactive aspect as it led to some passionate discussion on issues such as virginity, violence against women, and harmful cultural practices, among other issues. From that conversation, here are some profound statements I would like to echo:

- Why is a woman’s virginity so important to men when many men sexually abuse girls and women? Does a woman check if a man is a virgin before she marries him? “IT’S MY BODY, I OWN IT, IT’S MINE” – our bodies do not belong to men for them to decide what to do with it.

- African peoples have some harmful cultural and community practices that directly affect women and can destroy us, physically and emotionally. What is a culture when it destroys its own people? A true culture protects its people and does not expose them, especially marginalised populations, to harm.

- How do we break the cycle of violence against women? We need to put systems in place and ensure that they work. We will fight for our rights as women because no one will fight for us if we don’t. We should remember that power is not given; it must be expressed from within.

A fiery passion to transform this world and demand respect for women’s rights was borne in me this day, attending the conference and meeting so many young and courageous Feminists. It is important for us to sustain the dialogue on women’s rights and build support networks between young women so that we don’t feel isolated. It is good to have sisters around who will encourage and keep you.

Belinda Amankwah works at AWDF as a Knowledge Management intern.

AWDF Co-Founder Launches New Blog Above Whispers

AWDF Co-Founder Launches New Blog Above Whispers

AWDF Co-founder Bisi Adeleye-Fayemi has launched a new blog targeted at mature audiences.

Above Whispers is a space “primarily, (but not exclusively) for middle-aged women, and will provide an opportunity for people to engage in discussions about a range of issues such as politics, social justice, development, financial security, women’s rights, health, entrepreneurship, popular culture, faith, parenting and relationships.”

It hopes to offer a unique platform to engage with other people in an atmosphere of mutual respect.

Click here to read Bisi’s response to Nigerian writer Olatunji Ololade’s article on African Feminists “Beasts Of No Gender, The Nation.”

Bisi Adeleye- Fayemi, a feminist activist, philanthropist, social entrepreneur and writer, is one of AWDF’s co-founders.

Women Lead The Charge In Post-Ebola Guinea

Women Lead The Charge In Post-Ebola Guinea

CONAKRY, Guinea – A women’s cooperative saw its work almost reduced to ashes after years of work as the Ebola outbreak ravaged the West African country of Guinea, but the women would have the last say.Djakagbe Kaba has spent decades working towards women empowerment. Despite the setbacks during the Ebola outbreak, she is determined to reposition women at the forefront of agricultural development and lead the way to better earning power.

The women cannot be independent if they do not have the means

It is Friday in Conakry and the streets are busy. Vendors are selling their wares as passers-by haggle over prices, afternoon prayers at the mosque have already begun.

Amidst the hustle and bustle, Djakagbe Kaba, head of the women’s organisation AGACFEM (Association Guineenne pour L’Allegement des Charges Feminines), opens the boutique where the organisation sells locally-made products produced by the women they work with.

The shop is modest but Kaba is confident. She has spent the last 30 years working with women’s groups before she co-founded the AGACFEM in 1995. With a focus on training and women’s economic and political empowerment, AGACFEM has supported thousands of women living in the country’s rural areas.

One of the organisation’s early projects was a women’s leadership programme after receiving funds from the Accra-based African Women’s Development Fund (AWDF). Kaba and her team organised trainings for women to participate in local governance. By the end of the project seven women were elected as members of the municipal council.

But AGACFEM did not stop there. The programme extended to illiterate women, who were taught how to read and write and the importance of voting.

In recent times AGACFEM has pooled together a co-operative of 45 women’s groups in the rural areas Kissidougou, Guéckédou and Kankan. The Coopérative des Femmes Rurales pour l’Agriculture, la Souveraineté Alimentaire et le Développement (COFRASAD) spent the last four years training women in 10 villages in organic agricultural production and value-added processing and are currently in the process of completing the finishing touches to two processing centres. But when the Ebola virus hit in 2014 everything changed.

Kaba and her colleagues were forced to re-strategise. AGACFEM received another grant from the AWDF, this time for the fight against Ebola. The organisation decided to team up with three other Guinean NGOs – Coalition des Organisations pour le Rayonnement de L’Economie Sociale Solidaire en Guinee (CORESS), Cooperative Badembere and Association des Jeunes Agriculteurs pour le Developpement Communautaire (AJADEG) – some of whom are members of COFRASAD working in the same region that also received grants from AWDF during the Ebola crisis to put their funds together to tackle the crisis head on.

Kaba decided to leave the capital, Conakry, and base herself in Kissidougou for three months to ensure all the programmes ran efficiently. While she headed the project planning and budget organising, roles were allocated to her partners to ensure that they maximised their efforts and networks as they reached to villages across the region.

“When it came to making orders for hand-washing kits, we placed one order together to keep costs down.” Kaba points out that it was important to her that each organisation used its strengths. “For example,” she says. “Badembere is an organisation that manufactures soap, so we thought let’s put the money we have each been allocated to buy soap into Badembere to strengthen their capacities.”Kaba bought and bargained every item needed for the hand-washing kits, even down to the stickers on the bucket, to make sure the group got the best for their buck. After overseeing the manufacturing process, the kits would then go out to the villages with the women volunteers who were spreading the message about Ebola.

Though Kaba and her colleagues were successful in their efforts in distributing hand-washing kits across communities, raising hygiene awareness and communicating with people, the work they had been doing in agricultural production took a hit. Nothing was produced for a whole year, setting the whole project back.

“We had to stop production,” says Fanta Konneh Condé, the secretary general of COFRASAD and one of Kaba’s colleagues, as she overlooks one of the gardens in just outside Kissidougou. “We missed the harvest season.”

Fast-forward to December 2015 and work has restarted. Condé and her colleague, Mariame Touré of Badembere take a stroll through the garden, stopping to talk to the women, as they remark at how far they all have come. With babies on their backs and farming tools in their hands, some of the women are – for the time being – cultivating carrots, lettuce and chives. Once again working to provide for their families. Under the initiative, they also produce rice, cereals and potatoes.

Back in Conakry at the boutique, Kaba is sure of the direction she wants the co-operative to go.

“We want to increase production,” she declares, as she gestures towards the pots of shea butter and black soap on the shelves. “We would like to export these products.”

COFRASAD is expanding rapidly having grown from a co-operative of four groups after its first year, to 45 groups today, four years later.

“The women cannot be independent if they do not have the means,” Kaba says. “It is better to support a group of women, rather than just one.”

Read the original article on Theafricareport.com : Women lead the charge in post-Ebola Guinea | West Africa

ACSHR 2016 Accra, Ghana: Pre Conference – Foundations of African Feminism

ACSHR 2016 Accra, Ghana: Pre Conference – Foundations of African Feminism

AWDF facilitated a women’s only pre-conference session for the 7th Africa Conference on Sexual Health and Rights which took place in Accra, Ghana, from 8-12 February, 2016.

The meeting was jointly held with Curious Minds, Ghana, which acted as secretariat and conference host for this year’s gathering. AWDF wanted to provide a safe platform for an intimate and in-depth discussion of sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescents and youth. Aimed primarily at 15 – 30-year old women, it ended up being a mixed age group of both genders, which ignited some fiery discussion. But at the end of the day everyone agreed it had been worthwhile.

“We wanted to provide a safe space for young women to discuss the issues relevant to them around issues of SRHR,” said AWDF’s donor liaison specialist Joan Koomson.

The pre-conference session also looked at helping young women develop common strategies and messages on engaging effectively with issues during the conference, influencing outcomes and how to derive the maximum benefit from being there.

A Position Statement (see below), worked on at the close of the day’s activities, was presented at the opening session of the main conference held Feb. 11. It summed up the major concerns and aspirations of the young women.

Takeaway:

“Negotiating the space to have young women’s issues represented with government is a priority,” said Catherine Nyambura.

Kenyan Women Raise Awareness About HIV With Soccer and Cultural Extravaganza

Kenyan Women Raise Awareness About HIV With Soccer and Cultural Extravaganza

Youth, parents and even grandmothers came together for a day-long sports and culture fair in Nairobi’s Kibagare district hosted by Young Women Campaigning Against Aids (YWCAA), an NGO which focuses on HIV-AIDS prevention and advocacy.

The event, held January 27, was an opportunity for fun and games showcasing the group’s activities and handiwork, as well as an education day.

The day began with a gripping opening soccer match featuring grandmothers, guardians and parents of the girls, after which YWCAA’s team faced girls from other Nairobi teams, captivating all those present.

After winning teams were handed trophies, it was time for sensitization on drug abuse, Sexual Health and Reproductive Rights and HIV/AIDS. The active participation in the sessions showed clearly that the community both appreciated the information and wanted more.

“The event was a great success, with a higher turnout than we expected. The general public including the youth and adolescents were enthusiastic and actively participated during the question and answer sessions,” said Ms. Perez Abeka the group’s Executive Director.

Perez, who noted the personal growth of the girls within the organisation, commended several of them for their hard work, ambition and commitment to better themselves. It was the same commitment that propelled the formation of the organisation.

Working in bars helped shape the mindset of the early members of YWCAA who paid for their university education through part-time work as bar waitresses. This exposure opened their eyes to the socio-economic impact of HIV and the vulnerable nature of their work environment. Although the focus of the organisation was initially on bar waitresses, they’ve expanded their coverage to the youth, orphaned and vulnerable children and grandmothers.

The cultural extravaganza is the climax of a one-year project executed by YWCAA with funding from AWDF. The project seeks to use sports, culture and the creative arts as tools for prevention and advocacy on HIV/AIDS, and to serve as a means of empowerment for young women. The group’s participants benefit from an extensive mentorship program and training in various skills including dress making, bead work, beauty, hair dressing, drama and music.

YWCAA’s work continues to serve as an inspiration to the African Women’s Development Fund (AWDF) and the world at large.

World Health Organization Declares Ebola Outbreak Over In West Africa

World Health Organization Declares Ebola Outbreak Over In West Africa

January 14, 2016 – Today, the World Health Organization (WHO), declared the end of the most recent outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Liberia and says all known chains of transmission have been stopped in West Africa.

It’s a day to celebrate, yet the consequences of this outbreak – the worst the world has ever known, are devastating: over 11,000 deaths out of 28,000 infections in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, the three worst affected countries, and economies and lives shattered.

Liberia was first declared free of Ebola transmission in May 2015, but the virus was re-introduced twice since then, with the latest flare-up in November. The last confirmed patient in Liberia has tested negative for the disease following two consecutive 21 day incubation cycles of the disease.

“More flare-ups are expected and that strong surveillance and response systems will be critical in the months to come,” WHO said in a statement.

For us at AWDF who have been deeply involved with assisting women’s groups from the start of the epidemic, the welfare of women must continue to be a priority for local, government and regional leaders. The critical support which will be needed to get families back on their feet, children in school and health systems running, must not be denied.

“We need support for the women affected by Ebola and those involved in the fight,” says Djakagbe Kaba, who heads the Association Guineenne pour L’Allegement des Charges (AGACFEM), an AWDF grantee which was instrumental in coordinating Ebola prevention and education efforts in Kissidougou, one of the worst affected areas.

“After Ebola I hope we can help women resume their work in soap-making and agricultural production. Though the epidemic has passed, we must still be observant and remind people to always wash their hands. Preventive measures must continue,” Kaba said.

All our efforts will be needed in the months to come to ensure that the necessary prevention, surveillance and response capacity across all three countries are put in place and that more women are ready to shoulder responsibility in these efforts. Please make a donation now.

Silent Scream (A Tribute to Abused Women)

Silent Scream (A Tribute to Abused Women)

By Aisha Ali

(A Tribute to Abused Women)

Sunshine, Sunshine, Shining Through

Lighting up, the sky so blue

Sunshine, Sunshine, is it true

The tears you cry are red in hue?

Smiling, Smiling, a cheery face

Shining through from a secret place

Hidden from view, beneath the surface

A twisted, painful ugly furnace

Crying, Crying, silent tears

The soundless scream that no one hears

Broken, Tattered, a heart that fears,

Shadows jeering, mocking her cries

Mirror, Mirror, reflect the truth

From within our souls’ depth

Let us see the rot and filth

And break this destructive myth

Aisha is a writer and currently employed as a copywriter in Advertising. She is also enrolled at the University of Nairobi studying for a degree in Journalism and Media Studies. She has a strong interest in using social media as a platform to highlight, talk about and champion women’s rights issues. She believes that it’s a space for women who would otherwise be silenced, to voice their issues and build communities with each other. She uses twitter extensively, under the handle, @bintiM, to spark conversations on various issues facing Kenyan women. Aisha was a participant in AWDF’s 2015 Writing for Social Change Workshop in Kampala, Uganda.

Aisha is a writer and currently employed as a copywriter in Advertising. She is also enrolled at the University of Nairobi studying for a degree in Journalism and Media Studies. She has a strong interest in using social media as a platform to highlight, talk about and champion women’s rights issues. She believes that it’s a space for women who would otherwise be silenced, to voice their issues and build communities with each other. She uses twitter extensively, under the handle, @bintiM, to spark conversations on various issues facing Kenyan women. Aisha was a participant in AWDF’s 2015 Writing for Social Change Workshop in Kampala, Uganda.