Year: 2022

Awareness to Accountability; 30 years of 16 Days of Activism

Awareness to Accountability; 30 years of 16 Days of Activism

By: Martha Sambe, for African Women’s Development Fund

On April 29th, 2021, a 21-year-old Iniubong Umoren left home in Uyo, Akwa-Ibom, Nigeria, for a job interview. She never returned alive. At 4:29 PM that day, Iniubong’s friend sent out the first of several distressed tweets calling for anyone to help her friend, who she believed was in trouble.

Devastatingly, Iniubong was later found in a shallow grave within the family compound of Uduak Akpan, the young man who was eventually convicted of raping and killing her. Sixteen months later, a judge sentenced Akpan to death by hanging.

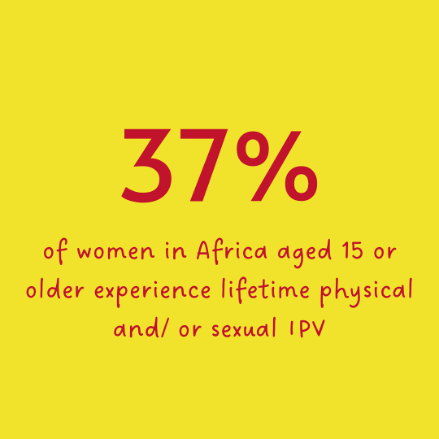

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in three women worldwide has experienced physical or sexual violence, mostly at the hands of an intimate partner. In sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of violence against women (VAW) by an intimate partner is about 33%, described as the highest in the world.

During the initial global response to the COVID-19 pandemic, this violence intensified to such an extent that experts began to speak of the “shadow pandemic”. For example, a study describing VAW across Africa in 2020 reported a 48% increase in East Africa during the lockdown. Similarly, according to the study, the Central African Republic saw an uptick of about 69% in reported injuries to women and a 27% increase in rape. Meanwhile, South African police also recorded a 37% increase in Gender-Based Violence (GBV) cases within the first week of April 2020. And in Nigeria, reported cases increased by 149%, a figure drawn from 23 out of 36 states.

A History of Violence

For 31 years, the world has marked the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence campaign from November 25th to December 10th. The campaign has provided a platform for concerted efforts to prevent and eliminate violence against women and girls. However, the origin of the movement goes farther back than is often mentioned. It was originally inspired by events in the Dominican Republic, when revolutionary sisters Patria, Minerva and Maria Teresa Mirabal were killed on 25th November 1960 by the authoritarian regime they opposed.

Twenty years after their deaths, in 1980, the first International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women in Latin America was declared. Then in June 1991, the Centre for Women’s Global Leadership (CWGL) and participants in the first Women’s Global Institute on Women, Violence and Human Rights called for a global effort against GBV and, in 1999, the United Nations formally declared November 25th the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women worldwide.

The Band-aid Treatment

More than 30 years after the first 16 Days of Activism, the world does not seem much safer for women and girls. According to the UN, crimes of Violence Against Women (VAW) are still the most under-reported, as well as being the least likely to end in convictions.

Nigeria’s conviction rate is evidence of this unfortunate phenomenon. In 2021, out of 5,204 reported cases of VAW, less than 1% of offenders (i.e. fewer than 52 perpetrators) were convicted. South Africa records a similarly low rate as 4,058 cases of GBV were reported in 2020, but only 130 convictions were made.

Needless to say, the speedy and decisive response in Iniubong Umoren’s case is not the norm. It was a rare victory spurred by the viral news of Ini’s disappearance, attracting attention from local and international press. This is not unusual; the more viral a case of VAW goes online, the quicker lawmakers and enforcers tend to act to lay the matter to rest. This trend also played out with the BBC Sex for Grades Documentary; less than a year after it premiered, the Nigerian Senate created and passed legislation against sexual harassment in institutions of higher education.

While these victories should be recognised, strategies for ending GBV need to go beyond reactionary approaches, which work only in rare cases. For example, it is known that GBV occurs due to gender-based inequalities, which often reflect an inherent power imbalance in favour of men, one that characterises many patriarchal cultures worldwide. Consequently, a reactionary approach to ending GBV tackles symptoms rather than the problem of inequality itself.

From Awareness to Accountability

The early years of the 16 Days campaign saw concerted efforts towards raising awareness about GBV. These efforts have proven successful, with the campaign now carried out across 180 countries worldwide, reaching 300 million people. After 27 years of raising awareness, in 2018, the founding organizations declared that subsequent 16 Days of Activism would focus on increasing accountability for VAW and eliminating all forms of discrimination underscoring gender-based violence.

A necessary step towards achieving this is ensuring that GBV is situated within the larger context of gender inequalities, thus providing a basis for a proactive stance. This intervention can look like providing support for the creation, implementation, and strengthening of legal and policy frameworks that address VAW while helping to bridge the gaps between law and practice through the creation of accountability mechanisms. Advocates and governments must strengthen the legal and policy frameworks which address VAW, and bridge the gaps between law and practice by enforcing accountability mechanisms. Since causal factors of VAW are often interconnected, interventions must be multi-institutional and multi-sectoral in their approach. Actors from the health, justice, education and security sectors all have roles to play in creating and implementing prevention-focused interventions.

Such work is already being done on the continent. For example, the ‘1-in-9 Campaign’ demands legal accountability and sustainable structural change through lobbying for the transformation of legal frameworks so that women and girls who report GBV can access justice. In addition, the campaign rightly acknowledges that ending VAW must include ending all other forms of oppression that impact women’s access to equality because all gender-based inequalities come from the same belief that women are subordinate to men.

Similarly, the Kenya Sex Workers Alliance (KESWA) is demanding accountability via a multi-sectoral approach that centres the safety and rights of sex workers. KESWA supports universal access to health services, including HIV services, and raises awareness through focus group discussions, social media campaigns, sensitization meetings and themed talks on gender-based violence. Furthermore, they work with the Kenyan police to influence a change in attitudes and foster accountability within the institutions.

At a regional level, the South African Development Community (SADC) developed a Regional Strategy and Framework of Action for Addressing Gender-Based Violence in 2018. As part of its key strategic actions to prevent GBV and protect survivors, the SADC has agreed to pursue accountability by ensuring that perpetrators are prosecuted and maintaining a culture of zero impunity by strengthening the legal and judicial systems. Similarly, provisions have been made to equip security personnel and increase their accountability for conducting evidence-based investigations and providing quality service delivery in GBV prevention and responses.

Getting it Right

As we commemorate 16 Days of Activism this year, I long for a future where women do not have to take out a few days to campaign against violence. But until then, we must broaden our activism beyond reactionary strategies that achieve justice for specific victims while thousands of others remain silenced. We also must recognize that VAW has a sociocultural basis. Thus, to make women and girls truly safe, we must create effective multi-pronged interventions that tackle inequality and oppression at the root.

Martha Laraba Sambe is a writer, researcher and intersectional feminist who believes none of us is free until we are all free. This article was produced as part of the African Women’s Development Fund’s (AWDF) 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence campaign, themed ‘Empowered People Taking Strategic Action to End VAW.’

Songs In The Future: AWDF 2021 Annual Report

Songs In The Future: AWDF 2021 Annual Report

We are thrilled to present AWDF’s 2021 Annual Report – Songs In The Future!

As 2021 waned, the DJs at AWDF belted out a playlist of beautiful compositions from all around the continent. Compositions that inspired us to journey together, recuperate and connect our steps throughout the year’s many layers. We invite you to join in reflecting on the futures sang by the many African feminist groups and activists we worked with in 2021.

African women’s rights and feminist movements were confronted with many manifestations of the patriarchy, and severe backlash. It was important to action our solidarity and utilise our position in various funder and policy spaces to articulate the morphing scope of the problem and what needed to be done.

With almost ten million dollars awarded in grants and donations in 2021, we were able to fund 64 new partners —a more than 11% increase from 2020.

We saw more bills passed into laws as women’s rights organisations shifted policy and practice to create enabling environments for women’s rights and the protection of activists. At the community level, partners celebrated individual behaviour changes as coalitions identified key influencers from groups originally opposed to the movement and negotiated meaningful partnerships with government structures. The campaigns we co-created rallied activist voices and sustained the visibility of major issues affecting African women’s rights on policy and resourcing agendas.

We recollect these experiences and more in a year where the songs of loss coloured the melodies of many places, yet together we rallied power to fuel each other.

Songs In The Future is a look back at the solidarity and strength of African women in their fight for freedom as they peered into an uncertain future with courage, dreams and hope.

You can access the full reports here

Rising in resistance against Fundamentalism: An East African Regional convening of African Feminists

Rising in resistance against Fundamentalism: An East African Regional convening of African Feminists

There is sufficient courage, resilient bonds, and wisdom to put up a resistance against the forces threatening our liberty

On a cool September evening, somewhere in Kampala-Uganda, a hall rang with peals of hearty laughter typical of old friends reuniting and the bubbly chatter of new friendships in formation. Wherever the eye rested, stirrings of joy abounded. In one corner, gifts of artisanal soap and scented candles passed from one hand to another, while in another corner, bits of news, personal and national, were traded.

These joyous sights and sounds belonged to a group of sixty African feminists who had come from Sudan, DR Congo, Uganda, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Kenya, and Rwanda to convene for the East African Regional Convening organised under the umbrella of the African Feminist Forum. At this forum, African feminists gathered to spend some time deliberating on strategies to counter the gale of fundamentalism sweeping across the world and with it, bearing seeds of conservative heteronormative patriarchal ideals, rigid homogeneity and fascism.

Fundamentalism often peddled through religion and culture can be defined as extremist and dogmatic interpretations of an ideology rooted in essentialist attitudes around various aspects of identity, like sex, ethnicity, religion, and nationalism. In the presence of perceived threats towards their identity, culture or power, those beset with a longing for the past where they believe “things were better back then” resist change, the advancement of modernity and any aspects of it. Often, this resistance takes place through the mobilization of people of a shared identity who are required to preserve or return to the past by putting up a spirited fight through strict adherence and enforcement of given rules.

Thus in the race towards maintaining homogeneity in regards to sex, gender and ethnicity etc, women’s and girls’ bodies which have long been ideological and political battlegrounds have their autonomy increasingly encroached upon as they are subjected to moral policing.

This year, for instance, we witnessed a surprising move by the United States Supreme Court when it overturned Roe v Wade, a landmark legal decision granting access to abortion to women in the US. This regressive move spells trouble for the rights of women, girls and gender-expansive persons in the USA and beyond, where organizing around sexual and reproductive health and rights will stall or fizzle out.

According to Open Democracy, US-based evangelicals, groups have poured more than $54M in Africa since 2007 to fight against LGBT rights, access to safe abortion, contraceptives and comprehensive sexuality education. This has resulted in some countries passing or attempting to pass discriminatory laws and practices as is exemplified by the anti-Homosexuality Laws in Uganda and now Ghana. In East Africa the Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Bill that could protect and facilitate the SRH and rights of all people in the region has stalled due to opposition by religious groups that are supported by Western fundamentalists. In August, 2022, by the Ugandan Minister of Ethics and Integrity in opposition to the bill said, “After all the failed attempts, they decided to sugarcoat it with some popular provisions, but when you assess it, you will find abortion, homosexuality, and these are not our values, this is not our culture, we said we must fight back,” said James Nsaba Buturo, the forum chairperson. A month before this convening, Kenya elected into power a president who is a well known evangelical christian who has given all signs of making religion central to his rule.

Away from religious fundamentalism, we have seen the rise of ethno-nationalist fundamentalism that manifests in increasing xenophobia and racism targeted against “foreigners” as in the case of continuos attacks against migrants in South Africa. In the Global North ethnonationalism continues to prevail in immigration laws intended to keep out foreigners, deportations or the detention of immigrants into modern day concentration camps like in Libya and Israel. The growing fundamentalist agenda is reflected in examples such as Sweden’s Democrat party which was founded by Neo Nazi movements, and the election of Italy’s far right prime minister who are meant to advance fundamentalist agendas.

Under the steerage of feminists of varying identities, the event ran from 25th to 28th September, and featured a profound discussion examining fundamentalism and how it manifests in governance, the economy, and individual spaces. These feminists are committed to the cause and are organising on various fronts; academia, grassroot movements, non-governmental organisations, political leadership among others.

Through its track record of oppression and destruction, fundamentalism as we have come to know it in historical and contemporary times, is indeed a fatal social poison that wounds and kills both the flesh and spirit. There’s never been a better time to take on this sinister force that is chiefly designed to subdue. The zeitgeist demanded that feminists convene to confront this wave of fundamentalism that was causing the rollback of the rights of women, girls, people from the LGBTQIA movement and other marginalised populations.

To infuse the participants with the mojo needed to take on the task of confronting and strategising against fundamentalism, the fiery Kenyan feminist scholar Dr Awino Okech, was elected for the task. Ahead of the reflection, Dr Okech set out to name the creature we were up against and lead us into a study of its anatomy before returning to the furnace to forge a weapon for it. Dr Okech offered much-needed insights on the subject through her keynote speech, pointing out that fundamentalism sits at the intersection of belonging, authoritarianism, and religious fundamentalism and that it takes on different forms in different contexts.

Using historical and contemporary examples at national and global levels, from Germany, India, Brazil and Kenya, Dr Okech explained that fundamentalism which often combines nationalism and religion, is a reaction towards the advance of modernity and also nostalgia for the past. She further pointed out that the advance of fundamentalism manifests in the form of moral panic that culminates in moral policing through surveillance and curtailing of civil liberties.

She shared examples of Iranian women protesting against the veil as part of their broader struggle for transformative justice, the election of a hyper-religious president in Kenya, Italy’s ushering in of a far-right political party and the overturning of Roe Vs Wade as clear indicators of the rise of fundamentalism. She submitted that given the nature of the kind of fundamentalism we are up against, it is only wise that our strategies against it take on a transnational, cross-movement and trans-disciplinary nature in order to defeat it. She encouraged us to stand in solidarity with each other, resisting on others’ behalf whenever their human rights are infringed on, because in preserving and protecting the liberties of others, we do our own. Our chances of survival and triumph over these forces, Dr Awino said, depends on how well we learn from the past. This means that we have to engage with the bodies of knowledge of our feminist ancestors to see the strategies that worked and failed and use that knowledge to forge our way forward.

Dr Okech’s keynote was a primer for the discussions that ensued at various feminist cafes set up on governance, economics and sexual integrity and bodily autonomy against the background of fundamentalism.

Ugandan Feminist scholar and educator, Sarah Mukasa submitted the need to create an ecosystem that responds to the issues at hand while learning from our past, to not lose sight of the bigger goal of social transformation. Professor Sylvia Tamale, a Ugandan feminist scholar and educator, in another rousing speech on decolonizing knowledge, implored feminists to engage vigorously with feminist writings and works and to write and document with equal verve so as to keep us flooding the past and our future with light. In support of this point, Dr. Awino Okech emphasised the importance of building and visibilising African feminist knowledge systems by citing African scholars. She called out young feminists’ inclination towards quoting feminist scholars from the west while ignoring African scholars entirely.

On resisting religious fundamentalism, Theology scholar, Professor Mombo Esther shared her thoughts on her work with the Circle of Concerned Theologians, a group of women theologians that dedicate their lives towards amplifying Pan-African and inter-religious theological perspectives of African women.

After days spent in collective reflection on the work to be done towards combating fundamentalism, the convening came to a close. At this point, the four days had cultivated an understanding that within and amongst us, was sufficient courage, resilient bonds, and wisdom to put up a resistance against the forces threatening our liberty. We felt that no matter how hard the fundamentalist gales blew, we would remain unbowed. In the joyous moments of exchanging words of hope and embracing each other goodbye, the words of Nigerian poet, Ijeoma Umebinyuo came to life:

“You call me sister not because you are my blood but because you understand the kind of tragedies we both have endured to come back into loving ourselves again and again.”

Written by: Mubeezi Tenda

Connect with AWDF at the SVRI Forum!

Connect with AWDF at the SVRI Forum!

Are you attending the SVRI Forum in Mexico this September? We will be thrilled to connect with you!

On September 19 until 23, AWDF will join hundreds of funders, researchers, practitioners to steer debate on the future of violence prevention and redress at the Sexual Violence Research Initiative (SVRI) Forum in Mexico, Cancún. The forum is the largest global, abstract-driven research and advocacy conference on violence against women (VAW). It brings together researchers, funders, practitioners, policymakers, activists, and survivors every two years to connect, learn and share. The forum is also an opportunity to learn about the newest innovations for prevention and responding to VAW in low- and middle-income countries and to meet some of the most influential donors, researchers and practitioners in the fields of VAW.

Our staff delegation will be led by AWDF’s Director of Programmes – Pontso Mafethe, together with a diverse team from our knowledge, grants and operations portfolios.

We are also thrilled to be convening over 20 movement voices from ten countries to actively engage and influence conversations in the space! These include representatives of women’s rights organisations, individual feminist activists and collectives on the continent and in the Middle East (from our Leading from the South programme).

Check us out at the forum by connecting with us at the following events and sessions

Connection highlight one

SVRI and AWDF collaborative donor engagement session on decolonised and ethical funding for VAW and gender equality

Tuesday| Sept 20 | 6:00 – 7:00 PM

Venue: TBD |Translation available: Spanish, English

Connection Highlight two

Dialogic panel: Power and control in research: The High-Income Countries – Low- and Middle-Income Countries Divide

**Chair: Pontso Mafethe, African Women’s Development Fund

Time: 16:30 – 18:00 | Wednesday 21, Sept

Venue: Goya | Translation available: Spanish, English

Connection highlight three

AWDF Grantee partners-led Knowledge circles

Wednesday | Sept 21 | 11:00 AM – 01:00 PM

Venue: TBD |Translation available: French, Arabic, Spanish, English

Connection highlight four

South-feminist led funding: Showcasing the Leading from the South Model

Thursday| Sept 22 | 14:30 – 16:00

Venue: Greco-Dalí |Translation available: Spanish, English

Here is the full programme of the SVRI forum where you will find details of these and other very insightful activities at the forum. Please contact our Knowledge Management Team via knowledge@awdf.org if you have specific questions around AWDF’s engagement at the forum.

Policy and Financing that works for African Women’s Sexual & Reproductive Health Rights

Policy and Financing that works for African Women’s Sexual & Reproductive Health Rights

After an incredible week of connection, construction and commitment with hundreds of feminists and sexual rights activists from across Africa, we are excited to share the Call to Action from the 10th Africa Conference on Sexual Health and Rights: ACSHR2022.

It is a collective call on governments, donors, feminist funds, Women Rights Organisations and the private sector to prioritise our recommendations to achieve greater impact in policy and financing outcomes for African Women’s SRHR.

Please download the CALL TO ACTION here, and SHARE!

Stay tuned for more updates and reflections from the conference.

Follow us on Social Media

Instagram: @the_awdf

Twitter: @awdf01

Facebook: AfricanWomensDevelopmentFund

LinkedIn: AfricanWomensDevelopmentFund

PROUD CONTINENT: A celebration of Queer Realities

PROUD CONTINENT: A celebration of Queer Realities

INTRODUCING THE PROUD CONTINENT ZINE

As a feminist organisation, AWDF provides crucial support to women’s movements working to end patriarchy, human rights abuses and gendered violence in Africa. Our core values of respect, diversity, feminist leadership, solidarity and partnership are demonstrated in the material, technical and institutional support that we provide to LBQT+ organisations fighting for the safety and freedoms of marginalised Africans.

This June, we have teamed up with our LBQT+ grantee partners in countries such as Angola, Tanzania and Uganda to highlight the experiences and convictions that shape the work they are doing. Our grantee partners are all courageous and committed individuals who work hard to secure rights, combat stereotypes and ultimately make society more welcoming for queer and trans people. These grantee organisations create safe spaces, provide much-needed healthcare and peer support, and mobilise around pressing issues in order to create a reality where all people are free to enjoy their human rights.

As we highlighted with our #LoveAndFreedomAfrica campaign last year, queer and trans people in Africa experience high and sometimes extreme levels of social isolation, physical and sexual violence, discrimination in workplaces and places of learning, and human rights abuses at the hands of the state and private actors. Trauma and suffering are however not the entire story of queer and trans life, and with the #AfriPROUD campaign we aim to highlight the complexity, beauty and courage that underpins the lives of our African LBQT+ sisters and siblings.

Pride Month is here and we see this globally recognised celebration as an opportunity to focus on LBQT+ Africans, while also reinforcing how crucial it is that we all act urgently to protect the rights and freedoms of our sisters and siblings.

We have compiled this Zine to spotlight the activism, resilience, and courage of Africans whose sexual orientation, gender identity, and social performance transcend conservative norms.

Proud Continent – June 2022 (English) by Square HQ

Connect. Construct. Commit. AWDF at the ACSHR Conference

Connect. Construct. Commit. AWDF at the ACSHR Conference

AWDF is excited to announce our participation at the 10th Africa conference on Sexual Health and Rights (ACSHR), which will take place from 27th June -1st July 2022 in Sierra Leone. The conference seeks to contribute to policy shifts, funding and solidarity around ending sexual and gender-based violence, promoting abortion rights and advancing the narratives of gender non-conforming people.

The ACSHR is a critical moment for human rights and gender justice activists, collectives and organisations to convene and recommit to shared goals, principles and promising practices toward promoting SRHR on the African continent. The conference is hosted by Purposeful and convened by the African Federation for Sexual Health and Rights in partnership with the Government of Sierra Leone, the United Nations Spotlight Initiative, partners across the Continent and co-programmed with the WOW Foundation.

AWDF will co-host a two-layered session, Policy and Financing Dialogue on Prioritising African Women SRHR that anchors the experiences of African women’s rights organisations, activists and influencers to steer policy and financing discussions on prioritising critical SRHR issues on the continent. The two-sequel panel session will start with movement voices amplifying the gaps, innovations and opportunities from front-lining SRHR initiatives and cascade into a high-level policy, financing and partnerships call to action that features policy and funding representatives.

The ACSHR aims to build a critical mass of feminist activists that are key for inspiring change towards scaling up the prevention of sexual and gender-based violence in Africa. It is also an opportunity to showcase AWDF’s work as an ally and resourcing partner for critical SRHR work and women’s rights organising on the continent.

Click here to book your tickets

We have an exciting line-up of speakers, performers, renowned African feminists including AWDF CEO Françoise Moudouthe.

Stay tuned for more details!

Holding Space for Consent Among the Youth in Ghana: A Drama Queens Story

Holding Space for Consent Among the Youth in Ghana: A Drama Queens Story

A yellow stranger creeps through the bars of my window

Reaching corners yet unknown to this poet

The refrigerator hums a dirge somewhere

But this one’s back is to me, and I am reminded

Of the weight of old souls in old skins or his breath

on a stretched skin like mine

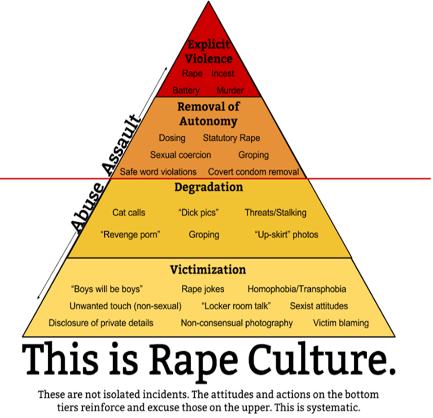

The global discourse on consent continues to deepen the understandings of other violations of personal space and forms of sexual violence previously ignored by legal statutes and sociocultural constructs that underpin rape and domestic violence.

Beyond its importance as a key conceptual learning tool for teaching sexual reproductive rights, consent affirms the dignity of all human beings especially to young people who continue to be affected by the lack of safe spaces to ask key life questions about their bodies and to learn ways of enhancing the quality of their “current and future” sex lives.

In Ghana, the discourse on comprehensive sexual (or sexuality) education has been met with overt reproach reverberated throughout the media from political and religious groups that moralise the initiative as ‘unsafe’ for adolescents and youth. They have claimed that such an education in self-awareness of their reproductive rights will gravely corrupt. However, this claim is disproved as Ms Hilda Mensah, a child protection specialist, shares in a 2021 interview that from the beginning of the year, one in five girls between 15 and 19 had reported experiencing at least one act of sexual violence in Ghana.

It is in this same thought tradition that teenage mothers are often blamed for their predicament for being “too fast”, more often than not ignoring the adult male perpetrator whose abuse of power in family or other relations with the victim has directly caused said predicament. The world reality of the youth is that issues about consent, bodily autonomy and sex are discussed by young people aged 13 – 18 both locally and globally through social media. Beyond such paternalistic assumptions by some adults, young people have some things to say about this and if their voices are centred in more policy approaches on sexual reproductive rights provisioning, some more effective training and learning can be achieved for transformational generational change.

Let’s Talk Consent is the brainchild of Drama Queens Ghana and was the main focal point for the trained volunteers and staff of the collective in 2017. Upon the request of various universities and high schools, the Let’s Talk Consent team offered a structured program on consent tailored to various groups of young people to hold space to discuss their concerns with some openness. What has been most enriching for our team, is learning what the general discourse is among some young people. Understanding the narratives that already persist among them, not only gave us a glimpse into the need for such conversation spaces to be held but also allowed us to tailor the workshops more specifically to address these areas.

For the young people who normally attended our sessions, we often got feedback about how they appreciated the space to talk freely and debunk the various myths they grew up hearing from their peers and society.

One noteworthy example, is a word exercise facilitated by our team that attempts to get young people to share some of the vocabulary with which they discuss sex and consent. Among some classes of teenage boys this referent language tended to be either blatantly violent or implied that one party was lessened by the experience and that was usually the girls involved. A male student once said “women who expose their body call for sexual attention” during the session in a bid to try and wrap his mind around what we were teaching and what he had learned from society.

The very aesthetes of consent when understood only through the lens of cis-hetero-patriarchal rape culture by young people especially those in high school, directly produces other instances of abuse and sexual violence. The normalised use of violent references for sex among young boys defies consent in circumstances especially where some activities are consented to and others are not, as we try to teach is the right of each party involved. By inviting young people to consider these are axioms, we attempt to demonstrate with the pyramid of sexual violence how micro-aggressions as subtle as benevolent sexism and harassment to overt actions such as obscene locker room talk, gradually builds a culture of acceptance and social approval which exposes mostly young girls and women to increased risk of violence and harm. Young people are constantly transforming into their fullest potential as adults, while being defined by and belonging to various communities with shared identities through whom they self-identify. These aspects of being, becoming and belonging are part of a childish-approach to children and youth policy studies. This considers the connections between key learnings in youth that affect later behaviour focusing on the perspectives of young people in discourse on their representations in policy frameworks.

Drama Queens’ work, at the very heart of it, attempts to address and combat societal ills; in this case, sexual violence, through varying approaches. These approaches can be through preventative activism, unlearning forums, or healing spaces. The Let’s Talk Consent branch of our work seeks to focus on preventative activism by encouraging people, most often the youth, to properly process human dignity, space and rights. In our sessions, we invite the participants to consider all the applications of consent in day-to-day life. The long-term goal, besides drastically reducing and possibly ending instances of sexual violence, is to make consent and its acknowledgement and acceptance, a default state of being for everybody.

One frequent comment we get during sessions is “But most girls (or people) mean yes when they say no to some advances?” (It is important to note that this question refers to instances where young girls and women, even though genuinely interested, are encouraged to appear coy and demure in a bid to not seem too eager by society). When this question is posed, we usually get a resounding affirmative feedback from the audience. This shows us that the issue of consent, just like almost all other societal structures, is very tightly-wound around sexism. Our response to this query is a firm, “Take a yes as a yes. And a no as a no.” We go on to explain that through no fault of their own, women (and “Assigned Female At Birth” AFAB folk) are taught to mirror a certain image in order to appeal to the male gaze. These instructions were received in various aspects of women’s lives; from their homes, religious involvement, romantic and platonic partnerships, to academic participation and self-image. In our work, we have come to realise that this may account for instances where women try to cover their interest with disinterest. All to project a sense of rareness and self-value. The very idea that women are made to tie their self-worth to such responses and behaviours is the very bedrock of objectification and we at Drama Queens are determined to let women (and AFAB) people know that they are worthy, they have the right to be their authentic selves and they are highly valued. By setting and creating a firm “yes is yes and no is no” culture, people, especially young people will take the first steps in thoroughly instilling a sense of candidness to self that helps to shed the toxic institutions women (and AFAB people) are brought up with.

Creating a safe space is at times underestimated, even by institutions who seek to have “modes of redress” integrated into their current systems and ways of operating. Unclear paths to proper justice for victims and “strict and unyielding” persons in redress systems, create an innate distrust for the systems” ability to properly address instances of abuse. In high schools for instance, in a bid to cut costs, institutions such as schools, place disciplinary-centred and hyper-critical teachers and staff in positions to hear student complaints and to act as guidance counsellors. The reasoning for this, aside from the aforementioned, could be that they trust such individuals to maintain the schools’ interest while basing their ability to adequately perform the tasks on their high “disciplinary rate” often obtained through harsh and insensitive means. This leads to students feeling distrustful and unsure of their institutions’ redress systems in the face of sexual assault / harassment. At Drama Queens, we understand the need for creating a safe space and we show this by asking our participants to put down rules that they would like implemented in their session to facilitate a safe space for them. In a safe space, participants may feel more inclined to share and have less fear of judgment for their thoughts, opinions and unlearning journeys (if they have their opinions on a certain topic, change during the session). This leads to altogether more productive sessions where participants feel more inclined to share and learn. Some of the rules participants come up with may include;

- No talking over others

- Do not make fun of peoples’ opinions

- No authority figures in the room

- Constructive criticism only

The vocalisation of these rules helps to shift uneasy dynamics in a session and could lead to students feeling safe with sharing their opinions and experiences, as well as being more conducive to take feedback and relearn ideas and concepts.

Our work spans various formats and we are dedicated to facilitating our activism through the various avenues we are granted. For the purpose of reaching larger audiences of different age groups and demographics in Ghana on the issue of sexual consent and everyday manifestations of patriarchal gendered norms, the stage play adaptations “For Coloured Girls: Who Have Considered Suicide When The Rainbow Is Enuf” and “Until Someone Wakes Up”, both attempt to stimulate thinking around these still taboo topics. In the former, funded by the African Women’s Development Fund and staged in the AWDF Sauti Centre, a select audience were thrilled to view a riveting show by our performers through monologues and live music on healing from the trauma of sexual violence. In the latter, staged on the occasion of International Women’s Day 2019 at the request of the Alliance Française and French Embassy as part of their fleet of activities for that period, our performers once again used thrilling scenes and dialogues to illustrate our stance on consent and sexual assault.

In breathing, existing, learning, being, people have been taught from very formative points in time to suit the norm. Our culture, as it stands now, is rife with rape culture. Existing within this current norm means to be complicit. Existing within this current norm is to choose easy. Doing the work to unlearn is hard. Unlearning and helping others to unlearn is also hard. However, what is activism if not passion in the face of difficulty? Drama Queens is committed to ensuring that we change the narrative. We are dedicated to the goal of progress, joy and mutual respect. Consent colours aspects of our existence beyond the sexual element and to understand consent is to understand respect. With constant thought analyses and constant unlearning, we can collectively ensure a better world that works for people especially for the most marginalised folks who have for so long been the victims of its continued existence.

We have unwound our wounds to become choruses- a vast sea swallowing the spaces between

where our stories sit in memory

Rainbow sheep who gnaw the thighs of the shepherd- our eyes hold ember

rechristened our fists into seedlings

Is this extracted from somewhere?

Written by: James S. Quarshie (Stage & Production Manager, Drama Queens) & Doris Odoi (Speakeasy Director, Drama Queens).

Poems by: K. Boat

Sexual Harassment in Digital Spaces: Sharing Experiences and Resources

Sexual Harassment in Digital Spaces: Sharing Experiences and Resources

Written by Emitomo Tobi Nimisire

I was thrilled to join social media the first time I did, eager to meet people – strangers who could become friends – and share my writing with them. I was fifteen. Social media exposed me to life-changing opportunities and gave me a few sustained platonic relationships (friendships?), but it also brought me an abundance of unsolicited photos of men’s privates, as well as name-calling and slut shaming. In my twenties now, I find myself reflecting on assault and harassment, and on how it has affected me. I think of all the times I have witnessed other women suffer this, and driven to properly understand this struggle, I created a survey. Here is what I found:

What counts as Online Harassment?

Online harassment includes any form of virtual interaction, action, or reaction that makes a person feel unsafe or discriminated against (Nimisire, 2021). According to Pew Research Center in a January 2021 survey, online harassment is measured by the following behaviours: offensive name-calling, purposeful embarrassment, stalking, physical threats, harassment over a sustained period of time, and sexual harassment. However, it is important to note that online harassment can be a subjective and personal experience.

Yasmin, an 18 year-old, says online harassment is “Everything pushy and forceful, done with the intent to harm. From stalking to persistent texting, sharing nudes, making up lies, blackmail, sending graphic pictures without consent, screen grabbing pictures and saving them (especially nude pictures).” Yasmin experiences some of these often because of her sexuality. She prefers to ignore harassers. For 19-year-old Mariam, online harassment is “Sending unsolicited dick pictures, someone constantly in my DMs trying to get me to sleep with them even after I’d already said No.” Mariam blocks and reports harassers’ accounts. “Trolling, body shaming, and doxxing.” These are what Cassandra, 22, considers online harassment. She mutes and blocks her harassers, or logs off the internet when she’s being harassed.

How is Online Sexual Harassment Violence?

Sexual harassment online can make a person feel threatened, exploited, coerced, humiliated, upset, sexualised or discriminated against. On many occasions, women and girls are harassed because of their gender and for having opinions. In another research in 2017, Pew Research Centre found that women are about twice as likely as men to say they have been targeted as a result of their gender (11% vs. 5%). Moreso, marginalised women are more at risk of online violence, especially LGBTQ+ people, sex workers, and women who are activists. 6 out of the 10 women and girls who filled my survey said they are harassed because of their sexuality. These indicate only a small portion of the targeted violence and insecurity that women are often at risk of in their daily lives.

Online sexual harassment encompasses a wide range of behaviours that use digital content (images, videos, posts, messages, pages) on a variety of different platforms (private or public) to harass or assault a person, ranging from unsolicited nude photos to rape and murder threats. A survey conducted by German advisory organisation, HateAid, shows that around 52% of women between the ages of 18 and 35 have suffered digital violence at least once.

There are largely four (three?) categories of online sexual harassment. These include: unsolicited sharing of intimate photos and videos; up-skirting — a situation in which a woman or girl is recorded without their consent; and revenge porn— where a video or photo is taken with the consent of the women but shared without consent. Other types of sexual harassment online include exploitation, unwanted sexualisation and sexualised bullying.

How has covid exacerbated online sexual harassment?

Use of social media increased following the COVID-19 pandemic, especially through the lockdown period. Movement ground to a halt, causing social interactions, workspaces, events, and engagements to move online. According to one survey, this directly resulted in an increase in reports of online harassment.

Impact of Online Harassment on Women and Girls

Silence: Survivors of online harassment are often scared into silence, especially in cases where non-consensual intimate images (NCII) are used to blackmail women and shared online, which may result in reputation damage. In less severe cases, to protect their privacy when harassed, women and girls change their privacy settings or deactivate their accounts.

Physical Insecurity: Survivors of online harassment may have a heightened fear of physical violence, especially if the harassers have access to private information such as their contact number, email address, or location. Research by Plan International conducted in 2020 across 31 countries with over 14,000 girls and young women about their experiences online discovered that more than half (58%) of those surveyed have been harassed and abused online, and 24% (that is, 1in 4 girls) are left feeling physically unsafe.

Psychosocial Stress: In the aforementioned report by Plan International, 42% of the girls and women who participated in the survey lose self-esteem or self-confidence, 42% feel mentally or emotionally stressed, and 18% have problems at school.

Loss of access to digital resources: In a society rife with rape culture and characterised by victim-blaming, when parents or guardians of girls who are being harassed online catch wind of the situation, they may limit the their access to the internet by seizing their mobile devices and computers. This in turn affects the girls’ education, professional and social lives.

How to handle Online Harassment

Report harassers’ content and account: Many social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have functions with which one can report abusive content and get support. You may also proceed to block the harasser’s account to prevent seeing their future updates.

Report to a local police station: According to the Nigerian Cybercrime Act 2015, child pornography and related offences – cyberstalking, racist offences, conspiracy, etc – are crimes that can be reported to the police and are punishable by law.

Be an active digital bystander: When a person is being harassed online, do not engage the content in any way, but instead report it and the harasser’s account. You may also check on the survivor to see how they are doing, offer support, or share helpful resources or tools with them.

Resources for combating Online Harassment

Feminist Internet is an organisation that intervenes in digital inequalities women and girls experience, and supports those who are discriminated against by providing tools such as Maru, an anti-harassment chatbot that helps with tackling online abuse.

EndTAB specialises in training people and organisations on how to navigate the digital abuse landscape via its online and live courses.

Web Foundation, with its Tech Policy Design Lab, is collaborating with tech companies and civil society organisations to create solutions for online gender-based violence.

As of 2020, 24 percent of Africa’s female population had online access, which means that about 161 million female Africans were at risk of online sexual harassment. This number has not remained static; more women and girls keep gaining access to the internet and will continue to do so. Creators of digital services and platforms must treat having effective policies that safeguard their users from online harassment as essential as the functionality of their products and platforms. We can no longer feign ignorance or turn a blind eye to the reality that our world now includes the digital world. Individuals must acknowledge that a person’s rights do not become non-existent the moment they get on the internet. The respect of the dignity of women and girls in the digital world is as important as their rights in the non-digital world.

About the Author:

Emitomo Tobi Nimisire is a Feminist Writer, Researcher, Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) Advocate, and Communications Strategist. She blogs at www.nimisire.wordpress.com.

Announcing the Ongea Mama Series

Announcing the Ongea Mama Series

[tp lang=”en” not_in=”fr”]

A COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE AFRICAN WOMEN’S DEVELOPMENT FUND AND BLACK WOMEN RADICALS

About The Ongea Mama Series

A collaboration between Black Women Radicals (BWR) and the African Women’s Development Fund (AWDF), “Ongea Mama” is an online series dedicated to curating discourses that uplift the unique perspectives, experiences, and activism of African feminists, from continental and diasporic approaches.

“Ongea Mama” translated as “Speak Mama” in Swahili. With this, the series is anchored around exploring major questions:

- What does it mean for African, Black, and Afro-descendant feminists to be in dialogue with one another?

- How can we learn from each other not only politically but personally, culturally, and even spiritually?

- How do we address and forge past historical and contemporary differences and tensions that impact our understandings of each other in efforts to create solidarity, sisterhood, and siblinghood across borders and boundaries?

- How can this series serve as a political education tool to learn more about feminist strategies, initiatives, and knowledge productions globally?

The “Ongea Mama” series is an extension of a previous event collaboration between the African Women’s Development Fund and Black Women Radicals which focused on “Health Equity and Power: Building Transnational Feminist Solidarity.”

As objectives, the Ongea Mama Series seek to

- Provide a dialogue and discourse among and between Africa, Black, and Afro-descendant feminists.

- Provide political education about historical and contemporary African feminist leaders and their leadership.

- Interrogate the work, activism, and productions of African feminists on the African continent and in the Diaspora.

- Create and build solidarity with and among Black women and gender expansive activists from around the world.

About The African Women’s Development Fund: The African Women’s Development Fund is a pan-African, women-led, grant-making agency that resources African women’s organisations to deliver sustainable development initiatives targeting women on the continent.

About Black Women Radicals: Black Women Radicals is a Black feminist advocacy organisation dedicated to uplifting and centering Black women and gender expansive people’s radical activism in Africa and in the African Diaspora.

[/tp]

[tp lang=”fr” not_in=”en”]

Une collaboration entre le Fonds Africain pour le Développement de la Femme et Black Women Radicals

A propos de la série Ongea Mama

Née d’une collaboration entre Black Women Radicals (BWR) et le Fonds Africain pour le Développement de la Femme (Rapport Annuel), Ongea Mama est une série en ligne consacrée aux discours qui mettent en valeur les perspectives, les expériences et l’activisme des féministes africaines, selon des approches continentales et diasporiques.

Ainsi, la série “Ongea Mama” traduit par “Parle Mama” en swahili s’articule autour de l’exploration de questions majeures telles que:

– Qu’est-ce que cela signifie pour les féministes africaines, noires et afro-descendantes d’être en dialogue les unes avec les autres?

– Comment pouvons-nous apprendre les unes des autres, non seulement sur le plan politique, mais aussi sur le plan personnel, culturel et même spirituel?

– Comment pouvons nous aborder et surmonter les différences et tensions historiques et contemporaines qui ont un impact sur notre compréhension de l’autre dans le but de créer une solidarité, une sororité et une fraternité au-delà des frontières et des limites?

– Comment cette série peut-elle servir d’outil d’éducation politique pour en savoir plus sur les stratégies, initiatives et productions de connaissances féministes dans le monde?

– La série “Ongea Mama” est le prolongement d’une collaboration précédente entre le Fonds Africain pour le Développement des femmes et Black Women Radicals, qui portait sur le thème “Équité sanitaire et pouvoir: construire une solidarité féministe transnationale”.

Les objectifs de la série Ongea Mama sont les suivants:

– Fournir un dialogue et un discours parmi et entre les féministes africaines, noires et afro-descendantes.

– Fournir une éducation politique sur les leaders féministes africaines historiques et contemporaines et leur leadership.

– Interroger le travail, le militantisme et les productions des féministes africaines sur le continent africain et dans la diaspora.

– Créer et construire une solidarité avec et entre les femmes noires et les activistes de l’expansion du genre du monde entier.

À propos de l’AWDF: Le Fonds Africain pour le Développement de la Femme est une agence panafricaine, dirigée par des femmes, qui octroie des subventions aux organisations de femmes africaines afin de leur permettre de mettre en oeuvre des initiatives de développement durable ciblant les femmes du continent.

À propos de Black Women Radicals: Black Women Radicals est une organisation de défense des intérêts des féministes noires qui se consacre à la promotion et à la centralisation de l’activisme radical des femmes noires et des personnes sans distinction de sexe en Afrique et dans la diaspora africaine.

[/tp]